2022 | Iron, stainless steel, galvanised steel, plastic, enamel plates / mugs, fabrics, faux fur fabric, threads, gauze bandages, crepe bandages, screen prints, masking tape, glue, acrylic paint, ink, wood, water, salt, vinegar, eucalyptus leaves and LED lamp | Display (width x depth x height): 118 x 118 x 118 in. / 300 x 300 x 300 cm. | Photos: In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres

After the Indian Army Corps arrived at the front in France and Belgium in October 1914, special hospitals for the Indian wounded were set up on the British south-east coast. One of these was located in the exotic palace known as the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, UK. Agar is dharti tay koyi jannat hai, o ay hi hai, ay hi hai, ay hi hai, is a large scale mixed-media artwork, inspired by a gigantic glass chandelier, that used to be suspended from the ceiling of the Dome within the Royal Pavilion. To this date, the Royal Pavilion has attracted visitors to Brighton, a popular seaside destination for centuries. But during the First World War, this exotic and ornate pavilion was converted into a military hospital called the Dome and Pavilion Hospital. This makeshift military hospital catered to the Indian Army soldiers, who were sick or wounded, whilst zealously fighting for the British. The pavilion’s first patients arrived in early December 1914. Over the following year, over 2,300 Indian patients were treated in an exuberant setting, which was in sharp contrast to industrial warfare, in the muddy trenches of the Western Front.

On the 16th of January 1915, an overwhelmed Sikh soldier wrote home from Brighton to an undivided India. As suggested on pp. 158-159 of Santanu Das’s book, ‘India, Empire, and First World War Culture: Writings, Images, and Songs’, the Pavilion Hospital reminds him of a couplet from the wall of the Diwan-i-Khas in Delhi, which he quotes in his letter, “Agar is dharti tay koyi jannat hai, o ay hi hai, ay hi hai, ay hi hai”. Translated into English, this line reads, “If there be paradise on earth, it is this, it is this, it is this”. Like the beautiful propaganda paintings and photographs of the hospital, set within the Royal Pavilion, these words obscure and repress the pain and reality of war, experienced by the Indian soldiers.

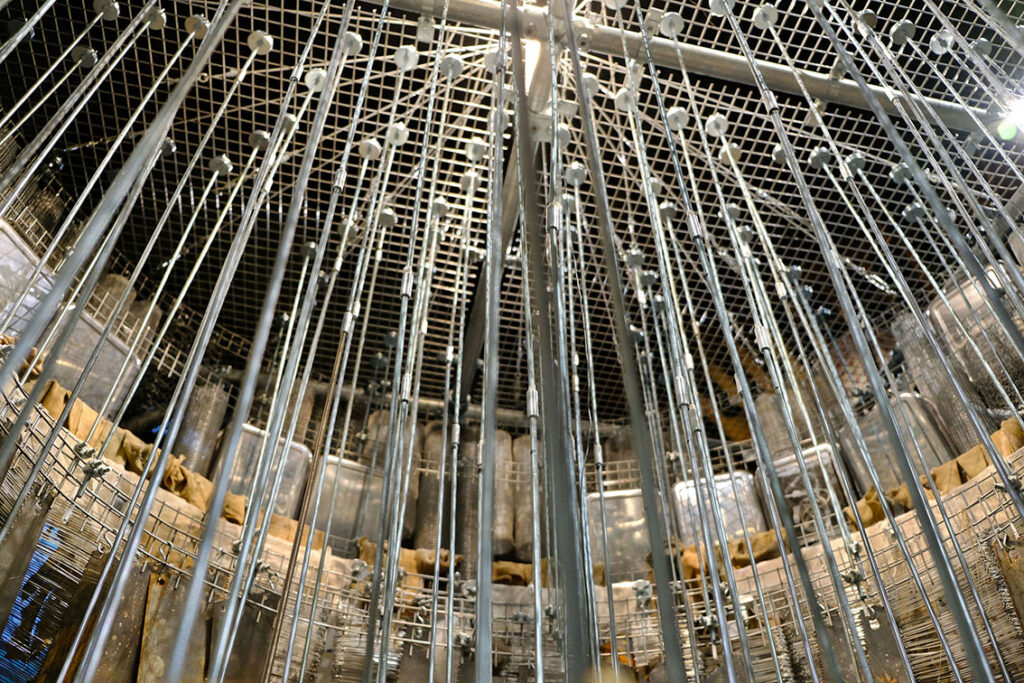

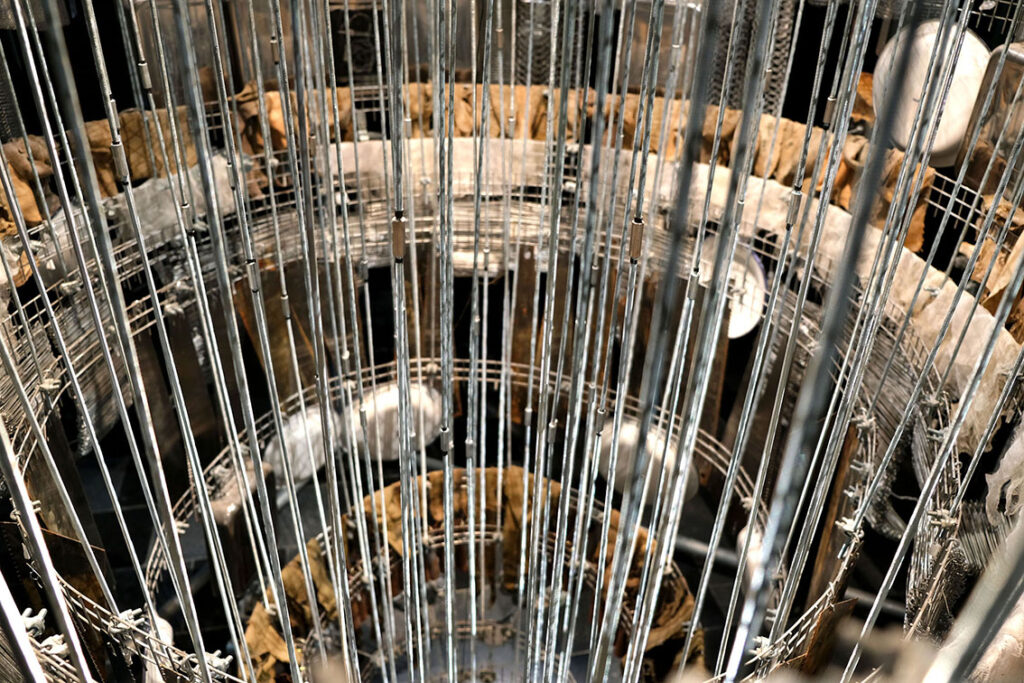

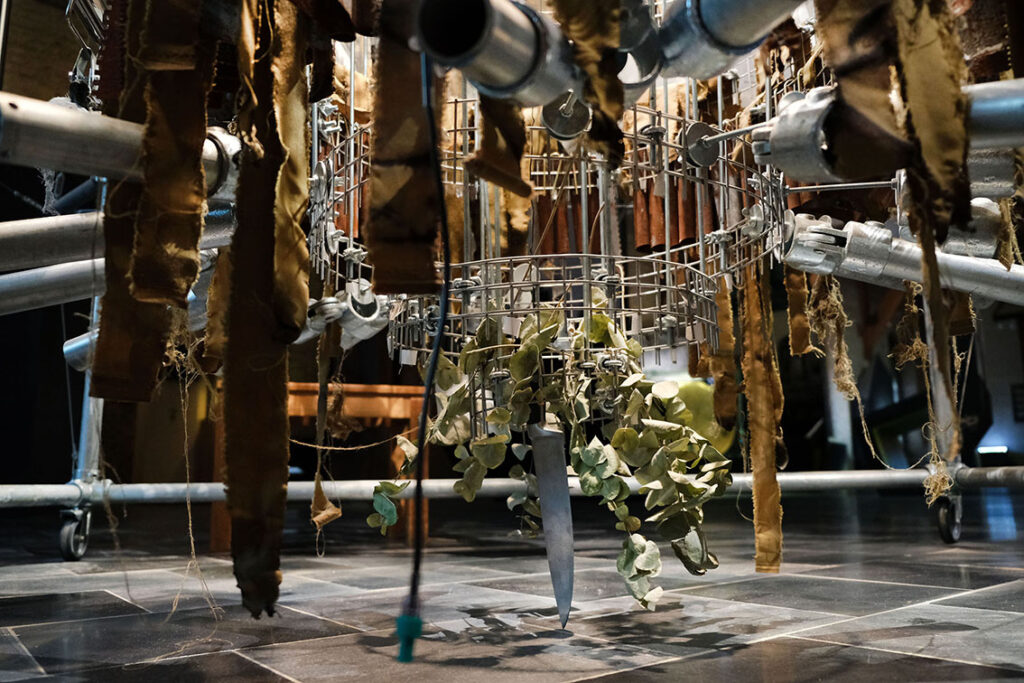

Taking the form of a circular chandelier, the artwork is not typically suspended from the ceiling, but rather held captive like a bonded prisoner – within a square shaped caged contraption. This enclosed structure, supported by metal pipes, and bound by cables was inspired by the actual fence installed around the hospital, to make sure the Indian ‘sepoys’ didn’t interact with local British women. Wheels were installed at the bottom to make the entire artwork mobile, like wheeled hospital beds and chairs within the Dome. The sculpture on wheels also emulates an oversized wind chime where the dangling of various objects produces a cacophony of sounds, that tries to echo the anxious and chaotic soundscape of a war hospital. The dense and layered labyrinth of metallic objects such as, pins, nails, hooks, blades, knives, chains, strings, handsaws, trays, mesh, pipes, rods, screws, nuts, clamps, all exemplify the violent nature of war. In contrast, objects such as stained gauze bandages, crepe bandages, burnt khaki fabric, faux fur fabric, taps, salt, vinegar, water, IV drips, eucalyptus leaves, enamel plates and mugs, gives us hope. They all remind us that healing and mending is possible, but not forgetting the violence and sacrifices that were made.

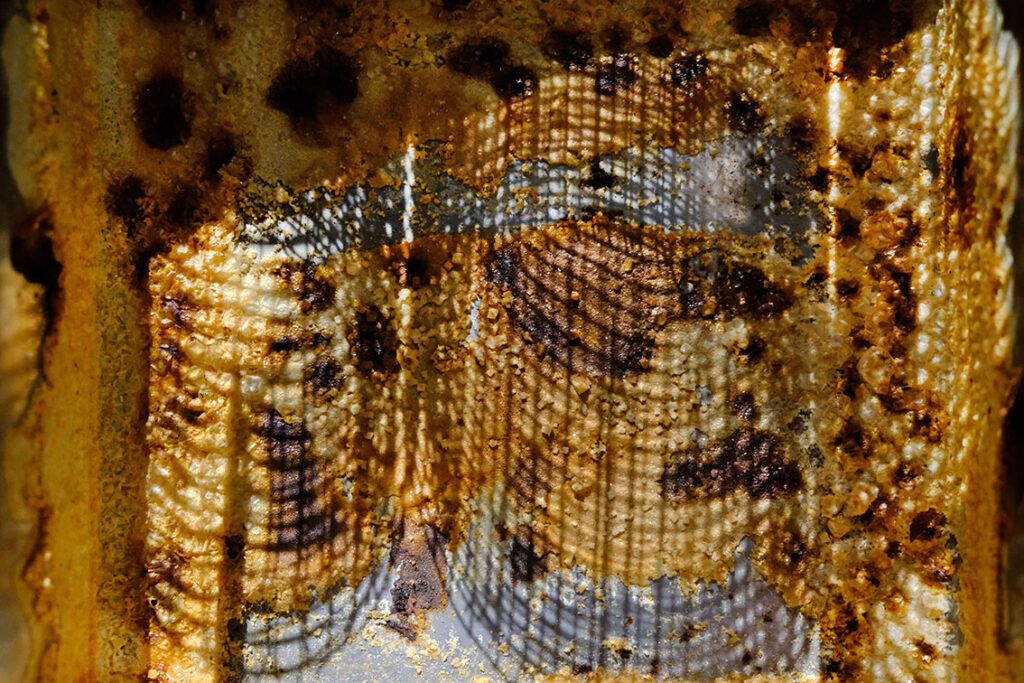

The artwork in the form of an inverted pyramid, also includes various numbers inscribed in Gurmukhi, Urdu, and Hindi with the help of pins on plates and trays. These numbers suggest the wages of the Indian soldiers, number of beds in the hospital, and so on. At times one can see the interior skeletal configuration of metallic rods and grids that holds all these clustered objects. A lone LED lamp suspended from the ceiling, looms over the cube structure. The lamp’s warm glow deliberately illuminates the inner sanctum of the chandelier to illustrate the brutal phenomena of war injuries, where bones, flesh and other organs are exposed. Next to the lamp are two pole-like armatures with cables tensed in 360 degrees around it, this mimics the enormous spherical shape of the Dome’s ceiling. Three water taps within the spectrum of objects, also indicates the three different water supplies for the Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh soldiers. Water pipes reminiscent of cannons are seen pointing towards us, and at the extreme lower centre of the chandelier, a sharp knife threatens the floor, reminding us that death looms over every soldier. Screen-printed images of wheelchairs, X-rays of body parts with bullet marks, IV drips on various surfaces are seen suspended and remain silent witnesses to the stories we will never know.

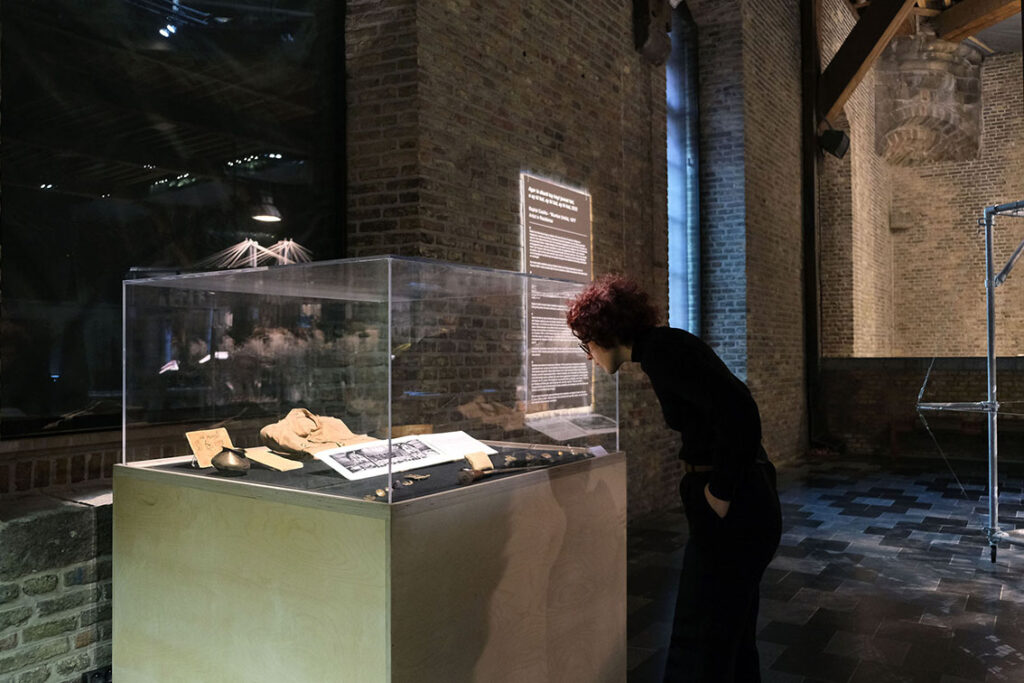

A vitrine consisting of various objects that inspired the artwork was displayed near it. Items used by Indian soldiers during the First World War, such as a khaki shirt, ‘kukri’ (knife), a metal ‘thali’ (plate) and ‘lota’ (water vessel), a language translation booklet, various epaulettes, etc. These items were all loaned by Dominique Faivre, from Saint Floris, France. The catalogue, ‘Indian Military Hospital Royal Pavilion Brighton 1914-1915’, issued by the Corporation of Brighton was the central object of the vitrine display. It consisted of photographs and text in three languages; English, Gurmukhi, and Urdu, and was given to each patient when they left the Royal Pavilion.

Agar is dharti tay koyi jannat hai, o ay hi hai, ay hi hai, ay hi hai, was developed during Baptist Coelho’s year-long Artist-in-Residence, supported by and at the In Flanders Fields Museum (IFFM), Ypres, 2022. The artwork was first exhibited at the IFFM, from 6 July 2022 to 8 January 2023. During the course of the exhibition, the artist made some additions to the artwork. For this purpose, a makeshift studio was set up in a discreet corner of the museum, not too far from the artwork. Thanks to IFFM; Fondation Fiminco, Romainville; Fonds de Dotation Buchet Ponsoye, Paris; Institut Français, India; Jan Radovan; amongst others.